Story

Call me Mr Mac

words mel jaunay

PHOTOGRAPHY sam kroepsch

Chalk dust and teenage anticipation season the air of an otherwise unremarkable transportable classroom at Nuriootpa High School.

It’s 1981, and a fit middle aged man with a neatly kept full beard, curly dark hair and glasses stands at the front of the class, preparing to address his first ever cohort of design students.

“I’m Mr McLauchlan,” he announces, only to be met with a furrow of brows as the teens size up this eccentric newcomer with his non-Germanic name.

Sensing their collective confusion, the man is quick to respond.

“Call me Mr Mac,” he says with a smile.

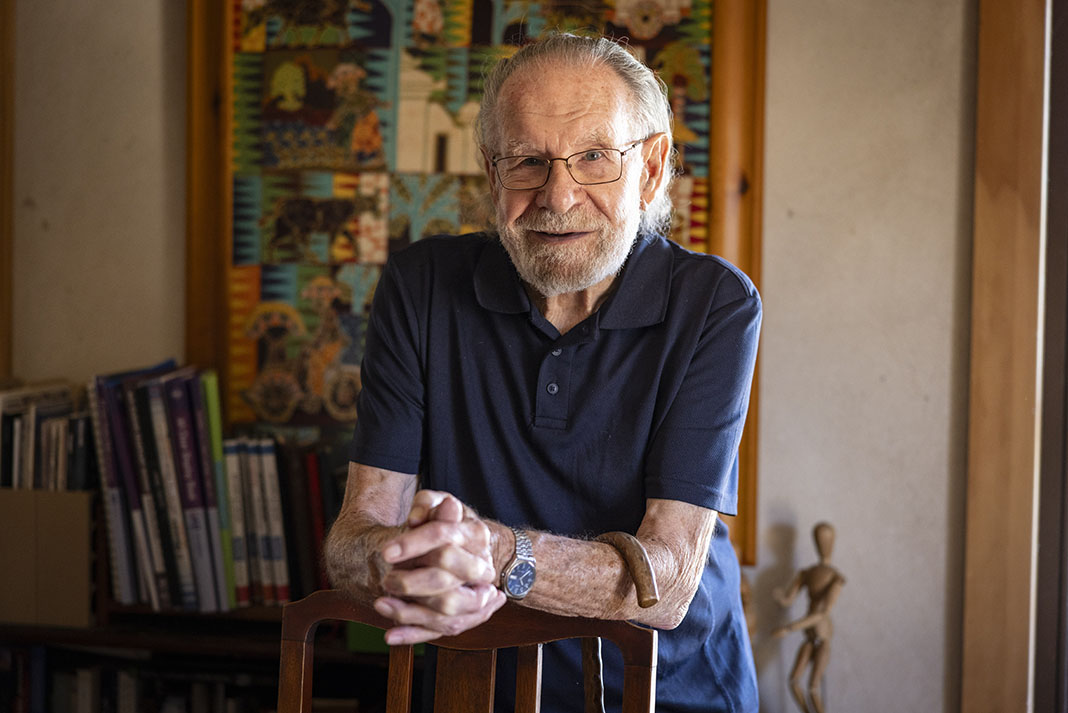

From that moment, according to the now 87-year-old John McLauchlan, the positive rapport between students and teacher only grew.

“It stuck, because you could see all these little faces light up as they thought, oh, he’s helping us,” says John, leaning back on a chair at his well-worn kitchen table, which is partially obscured by paint brushes, pencils, notebooks, small tools and trinkets thoughtfully organised into containers.

He jokes that he keeps everything, and the eclectic interior of his Bohemian Bethany cottage makes no liar of him—every shelf or surface is laden with books, sketches, collections, art supplies, pottery and curios.

But this is no unkempt hoarder’s roost, rather it displays the skill of a man who seems to walk an easy line between the creative and methodical.

“I was different, I was a different kid, that was one of the reasons why I did certain things in my teaching,” says John, taking a step right back to his days as a boy growing up in Broken Hill.

He was raised by his grandmother rather than his parents, for reasons not ever fully revealed to him, though he suspects it was something to do with money.

People were poor in those days, John explains, and his mother worked as well as his father, a handsome and talented man who was perhaps wasted in his vocation as an underground miner.

John keeps a faded photograph of him pinned to the board of his workroom. Through pale sepia, a tall, moustachioed man leaning intently over a sketchpad can just be made out.

“There’s my dad, drawing,” says John, adding his father wasn’t an artist, but he would have liked to have been.

Evidently, it was a talent passed on from father to son, as by age 10, John was drawing and painting with enough skill to be sent for lessons, although his lady instructor was a bully, who “couldn’t teach to save herself”.

Fortunately there were other teachers in John’s childhood who influenced him in more positive ways.

“To this day, the last teacher I had in primary school, I can remember his name: Jack Crossing. He was brilliant. He had a classroom of 35 boys and he taught every one to be better than they were,” recalls John.

It was an approach that no doubt stuck in John’s mind as he stood in front of that first class of teenagers some 30 years later.

But it was a roundabout way to get there, with more than 25 years in metal and technical design work beforehand.

At age 15, after receiving his Intermediate Certificate at school, John began work at the same mine his father worked at, Broken Hill South Ltd.

He did his apprenticeship in fitting and machining, and as John explains it, the work was a natural fit.

“I hooked in right off with it. Because even before then, I’m a maker. I make things,” says John.

“I just became very good at pulling things apart, putting them together, and making things for them… It was me. Simple as that.”

John became what was known as a “gun-fitter”, the guy who knew how to get the job done, quickly and with precision.

But his personality was often at odds with the bravado inherent in such a masculine workplace.

“I’ve never been very ‘blokish’. Some blokes I send right off. They want to punch me,” chuckles John.

Regardless, his quick wit and undeniable skill prevailed, and after about 10 years climbing the ranks in his first job, he moved on to other employment, including at another mine in Mount Isa, specialised hospital maintenance, and for a company that designed and made medical instruments, where his skill in design and drawing really came to the fore.

“I was trying to teach them drawing as a way of communication, as a way of thinking, and the other thing was, with design, was to learn to think.”

- John McLauchlan

But in 1977, John changed direction.

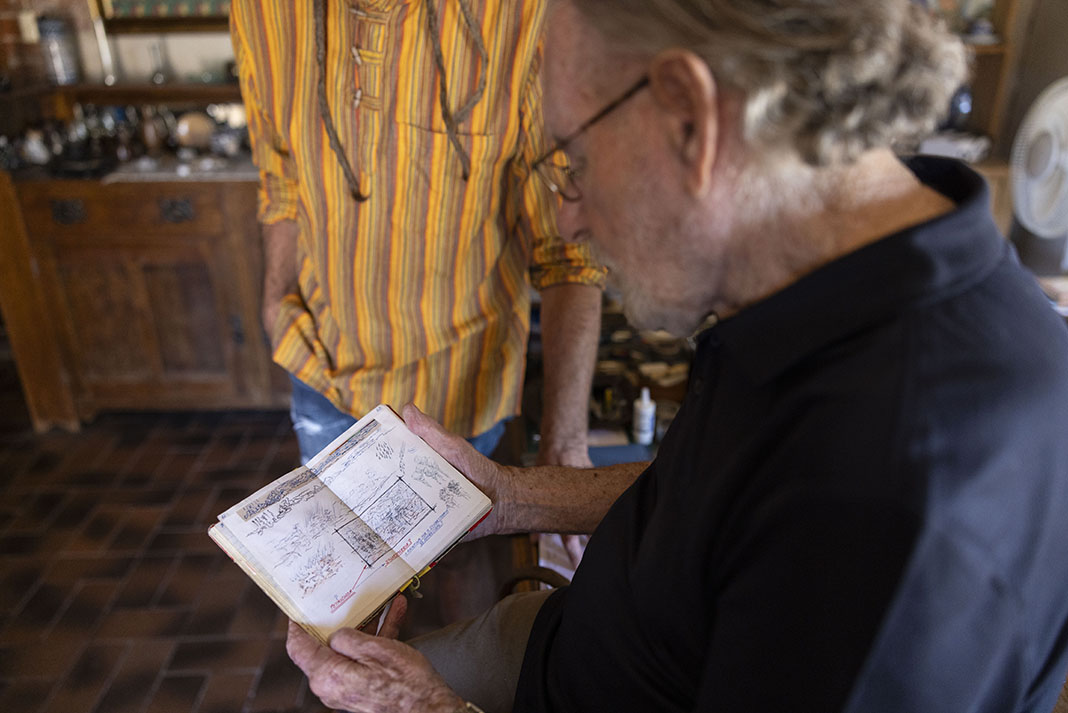

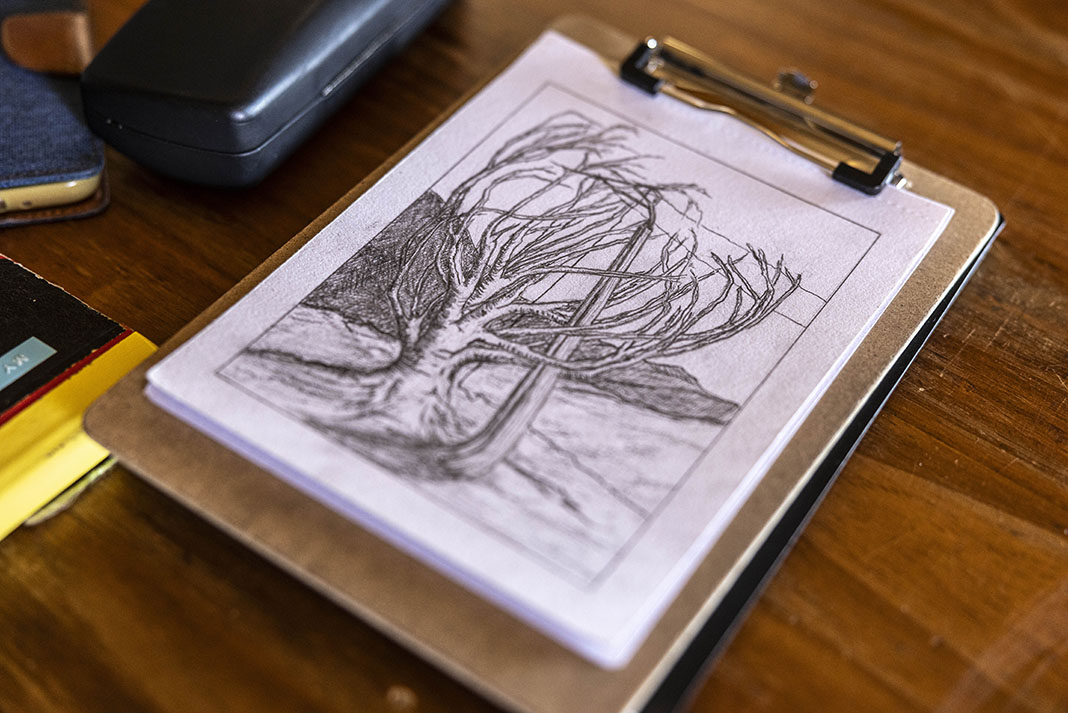

“Once upon a time back in ‘fairy land’, I wanted to be an artist,” John recalls, thumbing through dozens of sketchpads which reveal a lifetime of drawings: portraits, landscapes and patterns, some with soft lines and shading, others more geometric and stylised—all of it exceptional.

“I tried to get into university to do art teaching but they wanted design teachers… I was considered a designer, and (they thought) I’d be so good for them.”

He worked his way through a ‘Bauhaus’ influenced university course in Adelaide, impressing his tutors with his penchant for metal and design in jewellery making and other creative subjects, such as pottery and sewing.

But for a 40 year old male graduate from a rough neighbourhood, employment at the end of it didn’t come easily.

“As a teacher nobody wanted me. I was too old and I came from that place called Broken Hill,” says John.

It was Nuriootpa High School that eventually took him on, and over the decade that he taught there, his unique style of teaching, which included bringing in curiosities from other cultures and sketching caricatures of himself on worksheets, made him memorable to his students, many of whom have gone on to successful careers in fields of art or design, such as Marlo Grocke, Anna Seppelt, Stuart Hoersch, Kirsty Kingsley and Jamie Gladigau.

“My thing that I was doing, I was trying to teach them drawing as a way of communication, as a way of thinking, and the other thing was, with design, was to learn to think,” says John.

Stuart, a former art and design teacher and now visual artist, was a student of John’s in 1986 and 1987, and clearly recalls his mentor’s mix of firm-but-fair discipline, patience, understanding and wisdom, and the life experience and cultural knowledge he brought to the classroom.

“John used to enlighten us with quotes he had collated about art and design practice and thinking,” recalls Stuart.

“They were stimulants before the lesson to get our creative juices flowing… to rid ourselves of any inhibitions… to free our minds a bit. He got us working.”

Those quotes, poems and anecdotes, some about art, some about life more generally remain significant to John, who still carries the small, black notebook in which they are contained.

The passage of time has loosened the bindings, but the words, some belonging to others, some of his own, remain tightly woven in his beliefs and artistic inspiration.

“I have this thing, with drawings, especially, with landscapes and people and stuff like that, you have to capture the feeling of it,” he says.

Remarkably, despite his talent, John has only ever sold one painting of his own.

A portrait of a folk singer, it sold the first night it was displayed in a coffee and music lounge where John once worked as a ‘dishy’, to a man who paid a “rather good” price for an unknown artist.

It was perhaps a hint at what could have been, but with humble ambition, John instead chose a path of mentoring others in their creative pursuits.

Still, it doesn’t stop him drawing.

If not at home, sketching at his kitchen table, you might find him at a cafe, sitting, taking the world in, recording it just as John knows how.

“My best wishes to all of my students. May I have had a positive impression on them all,” he says.